Pedal Hard, Get Strong: Is Off-Bike Resistance Training Necessary? What Cyclists Need to Know

Today, we're diving into a study that challenges conventional wisdom about strength training for cyclists:

"Cyclists do not need to incorporate off-bike resistance training to increase strength, muscle tendon structure and pedaling performance: Exploring a high-intensity on bike method" by Alejandro Hernández-Belmonte and colleagues, published in Biology of Sport.

Listen to episode 17 of D-VELO-P cycling training podcast by clicking on the Spotify logo below.

The title alone caught our eye, especially because the high-intensity, on-bike training method they investigated—very short, maximal sprints—is something we frequently prescribe.

The 10-week intervention involved well-trained cyclists split into three groups, with two strength sessions per week:

On-Bike Resistance Training:

Five sets of 7 maximal sprints, each consisting of just seven pedal revolutions on a fixed gear two times a week.Off-Bike Resistance Training:

Five sets of seven squats at 70% of maximal dynamic force two times a week.Control Group:

Continued their normal training.

The groups were matched for training volume and intensity outside of the intervention sessions. The results offer strong support for incorporating maximal on-bike sprints into a training program, even over traditional gym work.

1. Strength Gains: Transfer is King

On-Bike Wins for Cycling: Both the on-bike and off-bike groups saw increases in their off-bike squat strength. However, only the on-bike group increased their on-bike strength. This suggests a strong transfer of power from the on-bike sprints to the off-bike squat, but a poor transfer from the single squat movement to the complex pedal stroke.

Use It or Lose It: The control group, which did no resistance training, actually saw a decrease in both off-bike and on-bike maximal strength. This highlights the importance of incorporating some form of dedicated strength work.

2. Joint Health and Comfort

Squats Increased Discomfort: The off-bike squat group reported an increase in both pain and stiffness over the 10 weeks.

Sprints Decreased Discomfort: The on-bike sprint group, surprisingly, showed a trend toward a decrease in pain and stiffness.

The Practical Implication: For cyclists with lower back, disc, or hamstring issues who find heavy squats or deadlifts problematic, the high-tension, on-bike sprint method is a highly beneficial alternative to achieve strength gains without the joint discomfort. You can focus your gym time on rehabilitative work instead of maximal lifting.

3. Neuromuscular Adaptations vs. Aerobic Gains

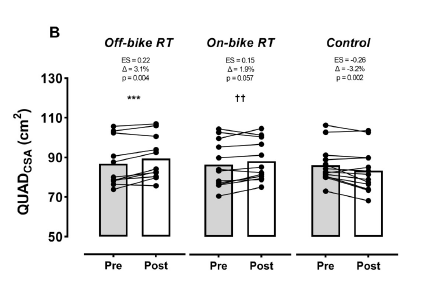

Muscle Cross-Sectional Area (CSA): Both groups saw quad growth, but it was only significant in the off-bike squat group (as seen in the figure below). While this might appeal to bodybuilders, a larger muscle cross-sectional area is not always desirable in an endurance sport like cycling.

Aerobic Markers: The study found no significant differences in highly aerobic markers like V̇O2 max, cycling efficiency, or time to exhaustion. This is expected, as the very short sprints are designed to target the neuromuscular system (the connection between your brain and muscle) and not the aerobic engine.

How to Apply On-Bike Strength Sprints

This type of training is all about neuromuscular tension, which is very different from long, low-cadence “torque” intervals (e.g., 3-5 minutes around threshold).

It’s Not Torque Training: Long, low-cadence intervals are great, but the loads are too low to be considered true maximal strength work. True strength training on the bike must be very short—ideally seven to ten pedal strokes—to maximize neuromuscular load.

The Crucial Role of Rest: Because you are training the nervous system and rapidly depleting stored ATP and creatine phosphate, rest is non-negotiable for quality.

Prescribed Rest: You need at least 2-3 minutes, and often 3, 4, or even 5 minutes of rest between each maximal sprint.

The Warning: If you rest for only 60 seconds, you might feel ready to go, but your peak power will decrease dramatically, negating the strength adaptations you are seeking. Keep the quality high by resting well.

Timing and Volume:

Don’t Overdo It: The study used five sets of seven-pedal-stroke sprints, done just once or twice per week. This is sufficient.

Vary the Stimulus: To train the neuromuscular system to be efficient and strong in all cycling situations, vary the sprints and don’t just focus on peak power:

Position: Seated (most time spent here), Standing, Aero.

Terrain: Flat, slight uphill, slight downhill.

Gearing: Over-geared (low cadence, high force) and “snappy” (higher cadence, still maximal force).

This training method is a crucial tool for any cyclist looking to improve maximal force and power transfer efficiently, with the added benefit of reduced joint discomfort compared to heavy barbell work.